Summary from Just and Lasting Change by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

An Example of SEED-SCALE in Arizona

Seed-Scale has been used by Native American communities to explore and assess their communal needs and resources and to advance development that stems from the community and reflects its needs and preferences.

The White Mountain Apache of Arizona have historically had mixed experiences of government neglect as well as government support, with government support often creating unsustainable relationships of dependency that undermined dignity and freedom.

Daniel Taylor reflects upon the history and culture of the Apache of Cibecue Valley:

“The two thousand Apache of the Cibecue Valley, in eastern Arizona, are the most isolated members of the White Mountain tribe. A high percentage of the people still speak the Apache tongue, and they try to keep the older ways alive. Older residents tell of idyllic childhoods spent in the forests with deer and other wildlife as neighbors, when Cibecue Creek still abounded with trout and beaver. They tell of times when women spent their days collecting plants for food and medicines while men and children spent their days on horses. Young people are encouraged to learn traditional stories, dances, and handicrafts and to take an active part in rituals that strengthen tribal identity and values.”

But this traditional way of life and its cultural integrity was aggressively disturbed over a century ago by the US federal government and its policies of ostensible ‘development,’ in ways that have had profoundly detrimental consequences for the community.

A top-down development model employed by the federal government led to decades of marginalization of the White Mountain Apache in their own communal development and resulting economic and social disadvantage that became structural and a defining feature of the community.

The Cibecue area remained little disturbed by outside intrusion until just after World War 1, when the US government came in with policies that changed both habitat and lifestyles. The first move was to sell grazing rights on Apache lands to non-Indians. The sale of too many permits resulted in severe overgrazing and extensive damage to the land. From the 1930s to the 1960s the government tried to turn the Apaches into cattle ranchers, worsening the damage. By the 1960s the adverse impact was clear, and the government decided to reengineer the landscape and, with it, the ecology.

This, too, was unsuccessful.

Less coercive federal government support for the White Mountain Apache that was prepared to share power and resources with the White Mountain Apache and to facilitate their ability to determine their own futures emerged in the 1990s. This followed many decades of inequality, underinvestment, indifference, and antagonism towards the rights, welfare, preferences, and cultural and communal integrity of the Apache community.

But after so many decades of federal government neglect and disregard, creating positive change was a struggle that entailed dismantling deeply embedded structural injustices and dysfunction in how the federal government interacted with the White Mountain Apache community.

Taylor writes:

“Few strategies to promote development have differed so starkly as those of the US government directed towards Americans of European origin and those directed toward Native American peoples: on the one hand, expansion of communications, education, health, transportation, and financial institutions; and on the other, confiscations of land, “assimilation” policies that involved removing children from their families and otherwise undermined traditional ways of life, and finally, “support” programs that promoted dependency instead of self-reliance. This latter history shows all too clearly how government actions that are controlling instead of enabling (even if well-intended) can do profound and lasting damage.”

The development assistance that the Apache community had received until the 1990s had been largely one that was imposed upon them rather than a reflection of their participation and involvement in its conceptualization, coordination, and execution.

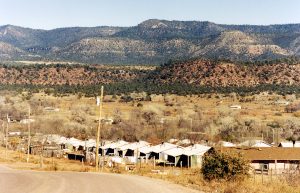

Fort Apache reservation settlement

As Taylor expands:

“Top-down development assistance interferes with building community capacity – even when done unintentionally to compensate for earlier exploitation… Local people need to strengthen their own capacities if they are to become real partners with government and experts in setting and implementing their priorities. To do these things all three partners need a systematic, regularly updated process and a commitment to cooperate.”

At the invitation of the community in 1996 – and partially as a result of the federal government finally becoming at least tentatively supportive of genuinely community-based programs of Native American community development – a study of the White Mountain Apache community was done by Taylor’s team. It concluded that new data showed that chronic diseases in the community stemmed from social factors that might not be considered directly health related. For example: the breakdown in relations between elders and youth, the lack of communication between men and women, and the decline of family gardening. These problems could be corrected only by behavior change, not by new clinics.

While the community did have adequate acute care in the form of a clinic, chronic diseases were not being addressed because of a healthcare bias focused on treating disease rather than enabling and sustaining behavior change and prevention of illness and maximizing health and well being through healthy lifestyle choices and behaviors.

Taylor writes about the results of their research with the community, in the community:

:The interviews revealed that the dominant health problems arose not from infections but from a sedentary lifestyle largely promoted by government welfare programs, from consumption of high-fat, high-salt, sugary “white man’s” food, and from easy access to alcohol. These health problems were very different from the ones being addressed by the good clinical treatment provided by the health center.”

The extent and severity of these problems were serious and causing major morbidity and mortality.

According to tribal estimates, alcoholism affected 40-60 percent of the people; 43 percent of hospital admissions and 42 percent of deaths between ages twenty-one and seventy-four were alcohol-related. In a survey of students aged nine to eighteen about 30 percent reported weekly use of alcohol or drugs as well as alcohol and drug addiction among their parents.

Using Seed-Scale, the Apache community was able to assess major gaps in healthcare programming and to determine how to address them through health programs focused on behavior change, improved educational opportunity, fostering intergenerational relationships between youth and older community members, and creating public services that would benefit the entire community and foster positive connections within it. These included constructing a laundromat and building a swimming hole. In determining that these were two projects that the community prioritized, Seed-Scale enabled the community to go beyond traditional forms of community development.

“Both the Laundromat and the swimming hole would have brought important health benefits, but neither directly fitted with the expectations of the Indian Health Service, which had hired us only to find out whether it should enlarge its clinic building,” Taylor writes. The Indian Health Service had already determined that the main health intervention was to be based upon acute care medial provision; Seed-Scale concluded otherwise and provided a necessary corrective to the Indian Health Service’s assumptions that did not match communal needs, preferences, and interests.

In reflecting on Seed-Scale’s impact on the development of the Apache community of Cibecue Valley, Taylor states:

“Today the Cibecue community of the White Mountain Apache is pursuing parallel pathways in education and healthcare to regain control over its own future. As a result of federal legislation over the past few decades, the tribal government is evolving increasingly effective community-based approaches in partnership with Washington and with independent experts of many sorts.”

Members of the White Mountain Apache Tribe marching to celebrate the 2004 opening of the National Museum of the American Indian.

The shift is long overdue and a long time coming, but it has finally enabled the Apache to direct their own development and in so doing, to improve their quality of life both as individuals and as a community.

“Our recommendations required a new approach, one that did not fit comfortably with established government practices, which make it hard for crossover action to occur among health, education, and environmental sectors even when solid research has made linkages clear. The Indian Health Service did, however, expand the Cibecue Health Center by constructing an adjacent Wellness Center and providing more prevention services.”

Taylor reflects that:

“When we began to work in Cibecue in 1996 we found that residents viewed the preceding decades of mostly well-intended actions as disrupting both to the environment and to the social fabric of Apache life. But the adverse outcomes were not all the government’s fault; Apache leaders, themselves unsure about the best course to follow, had generally gone along with government recommendations. There had been no enabling partnership to systematically build local confidence and capacity. Almost all projects had been driven by government paperwork and funding rather than by community work plans and a balancing of resources.”

It was Seed-Scale methods and principles that enabled the White Mountain Apache community to take control of their own communal development, and to ensure that it reflected their needs and desires and would enable genuine success at advancing health, well-being, and economic and social prosperity.