Melene Kabadege is a Rwandan health professional and practitioner who attended Future Generations University as a member of the Class of 2007. A nurse with a Bachelor’s in Public Health and 16 years working for World Relief’s health and nutrition programs, Melene was seeking a way to become a true Community Health specialist.

When she met Dr. Henry Perry in 2014, a member of the Future Generations faculty at the time, and learned about the University, she realized that her dreams of bringing positive and sustainable change to her community were more achievable than she thought. She credits her education here with building her knowledge and skills in community empowerment, social change, leadership, and how to leverage and lead community successes. This empowered her to bring about lasting healthy changes in her community.

Through the Master’s program, Melene became more confident in her abilities as an agent of change and sustainable development. This inspired her to start Community Fountain Project, an NGO with the purpose of working hand-in-hand with the community to improve lives. Community Fountain Organization is currently implementing the INEZA Project, which aims to prevent under-nutrition and reduce stunting in the Kamonyi District of Rwanda.

Farmer Field and Learning School

A member of Future Generations Global Network, as are all Future Generations graduates, Melene succeeded in winning a small grant from the organization in 2017 with the purpose of implementing a Farmer Field and Learning School. Here farmers serve as teachers to their peers and join together in a farmers’ cooperative. The Project areas of intervention were: improving farming techniques, improving nutrition in the first one thousand days of a child’s life, and improving saving and learning skills. Melene’s group worked with local leaders to ensure proper project monitoring.

Hands-On Nutrition Session

After six month’s of project implantation, the team noted several behavior changes taking place in the farmers’ households. Notable outcomes include: couples participating in nutrition learning adopted better nutrition practices for pregnant women and children under age two, families have improved hygiene and feeding practices, men have taken on an increased role in child care, improved farming techniques have been taught and adopted, farmers have been mobilized towards the operation and maintenance of community works, erosion control plants have been put into place, and 25 saving and lending groups have been implemented that all remain operational.

Voluntary Savings and Loan Program

At the end of the first year, the program has been considered successful and highly appreciated by community members and leaders alike. The project was implemented in 3 out of 12 Sectors of Kamonyi District. Fundraising activities are currently ongoing with the aim to extend the INEZA Project to cover all sectors of Kamonyi District and to become a learning center for community partnership in reducing stunting and improving the life of the vulnerable people.

Congratulations to Melene on her impressive work, and our thanks for sharing her story!

Make sure to follow the blog for more stories on the inspiring work being undertaken by our incredible alumni!

U.S. Series- Part IV: Conservation that Respects People and Planet

U.S. Series- Part IV: Conservation that Respects People and Planet

Summary from Just and Lasting Change by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

An article in Britain’s Guardian newspaper recently suggested that as much as 50% of the planet needs to be set aside from human habitation to stave off mass environmental degradation and irreversible destruction of animal and plant species.

The intention behind this argument is a good one: to conserve the earth’s biodiversity and natural life forms.

These have their own intrinsic value, but also ultimately benefit people in ensuring that natural resources are protected rather than exploited to the point of unsustainability; that air, land, and water are protected in ways that promote public health, and that global warming and other forms of environmental harm are mitigated.

But there is a fallacy at the heart of the notion that the primary way to advance conservation is by removing people from nature.

People and nature are not necessarily adversaries. There are many examples, including contemporary ones, of people serving as successful guardians of nature, rather than as antagonists to the environment and its conservation.

The misguided notion that people and nature are adversaries has sullied conservation since the incarnation of the modern conservation movement. It needs to be acknowledged and addressed because it both hinders and slows environmental conservation and can contribute to denying the human rights of people who depend on nature for their livelihoods.

For many people, as individuals and as communities, their lives, values, and cultures are intimately and inextricably bound with nature.

U.S. Series- Part III: The Green Bay Packers: Community-Owned Energy

U.S. Series- Part III: The Green Bay Packers: Community-Owned Energy

Summary from Just and Lasting Change by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

When you think about football, chances are you don’t think about community development, shared resources, a commitment to a non-profit ethos, and a cooperative approach to owning and managing a sports team.

But there is an open secret about one American football team that, while famous for the quality of its players and the passion of its supporters, should also be famous for its communitarian spirit, structure, and values.

As the Green Bay Packers By-Laws state, ‘The association shall be a community project intended to promote community welfare and that its purposes shall be exclusively charitable.”

This challenges the dominant paradigm of what drives sports in America and around the world: profit making. Sports are big business and they are, for the most part, run as big business.

But there are exceptions.

And it turns out that while the Green Bay Packers do make money what they do with that money and how they reinvest it in their community is what is so unique and notable, beyond their sporting excellence.

As Paz Magat, the author of this chapter in Just & Lasting Change, writes,

“The Green Bay Packers are one of the most iconic teams in American football, a team that has won thirteen championships – more than any other American professional football team – and a team that comes from the smallest city of any professional football team. So how is this team a charity? How does it promote community welfare? The answer is that instead of making money, the purpose of the team is winning for the community.”

U.S. Series- Part II: The Lesser Known Lincoln

U.S. Series- Part II: The Lesser Known Lincoln

Summary from Just and Lasting Change by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

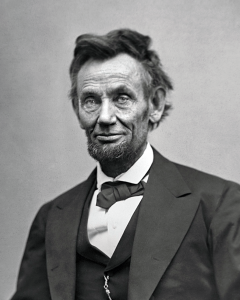

About Abraham Lincoln so much has been written it appears unlikely that there is more to say about him that might be new to readers. But, there is a part of Lincoln’s legacy that is genuinely underexplored and not widely known and it merits attention.

Lincoln was committed to advancing human development in a young United States in a way that was deeply democratic, progressive, and marshalled human resources in innovative ways that were ground-breaking and far-reaching for his time. The legacies of the policies and programs he advanced remain as defining features of American life today, and he had an animating vision of unity in diversity that informed those policies and programs.

We take the holiday of Thanksgiving for granted; it has become one of the defining features of American cultural life. Whatever one’s religion, ethnicity, politics, heritage – wherever one comes from – Thanksgiving is widely celebrated by a huge cross-section of Americans.

What many don’t know is that we owe Thanksgiving to Lincoln, who set it aside as a holiday of thanks that he had the foresight to recognize would unite Americans despite their many divisions. To this day, it continues to do so and to bind Americans across boundaries of difference, both real and imagined, small and profound.

U.S. Series- Part I: The White Mountain Apache: Reclaiming Self-Determination

U.S. Series- Part I: The White Mountain Apache: Reclaiming Self-Determination

Summary from Just and Lasting Change by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

An Example of SEED-SCALE in Arizona

Seed-Scale has been used by Native American communities to explore and assess their communal needs and resources and to advance development that stems from the community and reflects its needs and preferences.

The White Mountain Apache of Arizona have historically had mixed experiences of government neglect as well as government support, with government support often creating unsustainable relationships of dependency that undermined dignity and freedom.

Daniel Taylor reflects upon the history and culture of the Apache of Cibecue Valley:

“The two thousand Apache of the Cibecue Valley, in eastern Arizona, are the most isolated members of the White Mountain tribe. A high percentage of the people still speak the Apache tongue, and they try to keep the older ways alive. Older residents tell of idyllic childhoods spent in the forests with deer and other wildlife as neighbors, when Cibecue Creek still abounded with trout and beaver. They tell of times when women spent their days collecting plants for food and medicines while men and children spent their days on horses. Young people are encouraged to learn traditional stories, dances, and handicrafts and to take an active part in rituals that strengthen tribal identity and values.”

Bending Bamboo

Bending Bamboo

By Katie Larson

When do we learn about sustainable development?

How do we learn about sustainable development?

Who is this we that I keep mentioning?

Is sustainable development only a topic for development professionals?

Even if we learn about sustainable development as children, which children get access to the “juicy”, life-changing content, produced by the United Nations, climate scientists, and development professionals?

If you speak English, you can easily access this “juicy” content. If you are confident in English, you can go further and sift through this content. If you have cultivated your critical thinking skills, you can go even further and compare the content you are reading with the reality of sustainable development in your context.[1] Think Bloom’s Taxonomy. Then think about how English fluency fundamentally impacts who gets access to the knowledge critical for understanding and meaningfully supporting the health of our changing planet.

Now, what if you are not confident in English? Imagine that you can’t sift through the many amazing resources available on sustainable development. Maybe the only content you can access is general information. You know what I mean, the information that explains that if we drive our cars less then we can stop the polar ice caps from melting and save polar bear habitats. Two very important issues to solve, yet, superficially examined and far from many people’s day to day realities.

Those of us in the development sector know that sustainable development has many definitions and that its diverse definitions, applications, and manifestations are a result of complex contextual realities. Yes, sustainable development is certainly a concept to associate with solutions to climate change. However, sustainable development as a solution must be understood in context, in a way that values local economics, health, infrastructure, and all of the other important topics of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Here is where the study of language and the study of sustainable development are similar. According to the Communicative Approach in language learning, when learning how to communicate in another language, the learner’s context matters. Imagine you are a 10th Grade student living in rural Vietnam with a high likelihood of never traveling outside of your country. You go to English class (a required subject) and open up your textbook (published in London) and scan the lesson. The lesson asks you to imagine you are discussing your recent trip to Piccadilly Square in London. What did you see? What did you eat? How were the British people? Now ask yourself, am I going to be engaged in learning how to communicate with this kind of content? Also ask yourself, will this lesson give me skills for a future career? Students who cannot link content to context and who see no relevance in learning about things they don’t think will help them in the future, are not going to seek greater fluency in a foreign language. With content unconnected to context and irrelevant to the student’s future, English language study becomes a tool only for those few students who think they will travel and/or find employment outside of Vietnam. But the truth is, English is a global language. It can be used in rural and urban Vietnam to connect people, business opportunities, science, and funding from around the world. It can also be used to foster international collaboration on sustainable development solutions for communities.

The process is the same with sustainable development knowledge acquisition. What if the content you access is tooooo unconnected to your context? What if you don’t have the English skills to sift through the content? What if you don’t have the critical thinking skills to compare and contrast content with context? Will your sustainable development education equip you to visualize sustainable development in your context? For many, the answer is no. Arctic ice problems are important. However, if they are presented as an isolated challenge, they will seem like frivolous topics of study for someone living in a tropical river delta…say the Mekong River Delta. And those of us fluent in sustainable development know just how connected the ice caps are to our oceans and the river deltas that neighbor oceans. With superficial sustainable development education, students exit school without understanding the ways in which their actions and future careers might help or hurt Earth’s ecosystems.

Now, I have a BIG question regarding English fluency as a tool to access, sift through, and critically think about sustainable development. Can we drive English language acquisition while driving sustainable development knowledge acquisition?

This is a question that Bending Bamboo is trying to answer.

What is Bending Bamboo you might ask? Bending Bamboo is a process for acquiring intercultural, communicative, competence, confidence and collaboration (iC5) skills in English and sustainable development. Bending Bamboo does this by connecting English and sustainable development to context. It currently operates in Can Tho, Vietnam – the hub of the Mekong Delta. Over a two-year cycle of workshops and online forums, Mekong Delta teachers and professionals work together to acquire their own iC5 skills and then create a curriculum that teaches these iC5 skills to their students and employees. The first deliverable of this cycle is a teacher text. The next is a student text. Both incorporate local research on sustainable development in Vietnam and South East Asia. Both incorporate the knowledge of the teacher, farmer, tour guide, and corporate professional. They both seek to support English language and sustainable development knowledge acquisition.

In its most recent workshop in July, Bending Bamboo began to visualize a concrete answer to this BIG question.

During 60 hours of workshop learning, participants were introduced to sustainable development information and stories from local and global perspectives, in English. Local and foreign experts were brought in to share their science with the participants, in English. As proficient English speakers already, the participants could sift through the content of the workshop. Tasked with reviewing and comparing sustainable development content from here and there, teachers also cultivated their critical thinking skills. For 18 participants, this was their second Bending Bamboo workshop. For these 18 participants, post-workshop evaluations showed that both their communicative English confidence and sustainable development knowledge confidence grew!

That’s good news. Bending Bamboo participants are citizen-leaders in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam. They are knowledge bridges for their communities. These citizen-leaders are now critically interacting with local and global sustainable development discourse. Even better, these citizens are, inherently, strategically positioned to spread their knowledge. Bending Bamboo is currently leveraging this strategic positioning through the collaborative creation of the Bending Bamboo Teacher Text for grade 10-12 teachers in Vietnam. Next is the collaborative creation of a Bending Bamboo Student Text for Grades 10-12. With these two tools, participants and the Bending Bamboo team can tangibly impact a student and citizen’s ability to access and meaningfully engage with sustainable development discourse.

As Bending Bamboo continues to answer, through data, its BIG question, it also eagerly and intentionally looks forward to answering the next question. It is a BIG BIG question. Can the integrated Bending Bamboo curriculum not only drive communicative English and sustainable development knowledge acquisition, but also drive sustainable development action?

Now, just for fun, I shall end with two more questions. These are BIG BIG BIG questions to get you excited and thinking about the potential of creating and implementing, context-driven, quality education. Approximately 50% of Vietnam’s population is under age 25[2]. What happens when Vietnamese youth are confident in integrated iC5 skills for English and sustainable development? What impact will this rising generation of Vietnamese citizens have on their provincial, national, ASEAN, and global communities?

[1] Interested in this statement? Read: Powell, Mike (2006). Which Knowledge? Whose Reality? An Overview of Knowledge Used in the Development Sector. Development in Practice, 16(6), 518-532.

[2] From the General Statistics Office of Vietnam

Development Series- Part IV: Advancing Human Development in Kerala, India

Development Series- Part IV: Advancing Human Development in Kerala, India

Summary from Just and Lasting Change by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

Human development that significantly advances quality of life does not have to be expensive.

It is often assumed that to make major advances in the quality of human well-being development efforts that address healthcare, education, food security, and the well-being of women and children are necessarily extremely resource intensive and therefore dependent on massive outlays of funding to advance human security.

But this is not the case.

Successful forms of development that have been transformative in positive ways and are well documented in development literature show that human well-being can be advanced with basic resources that can be found in most communities, including in countries that lack financial resources and are classified as low income.

Put simply, financial wealth is not a prerequisite for fundamental human development.

More significantly, trust, cooperative communal efforts to pool resources and expand them, careful and equitable planning, and support of local and national government coupled with local grassroots efforts are often sufficient to advance human development.

These advances lead to tangible improvements in life expectancy, improve quality of life and enhance health outcomes, promote the realization of the human rights of children and women and human rights more broadly, expand educational opportunities, and raise incomes and improve food security.

How is this possible and where has this been done? In Kerala, India.

Kerala, a region of South India, made huge advancements in human development without being dependent on external aid for enabling this transformation.

Kerala achieved the best health and education levels of development in India already by the 1960s, and continues to sustain them, while also maintaining the highest rate of political participation in India.

But, counterintuitively, it was also the poorest state in India when it had these dramatic health and education achievements.

In this seeming contradiction we can find vitally important lessons about advancing human development which may be counterintuitive, and for that reason merit attention.

Development research attributes Kerala’s outstanding social achievements to several factors.

Daniel and Carl Taylor, pioneers of community development together with UNICEF, explain that these include political leadership that was largely genuinely interested in advancing the welfare of Kerala’s residents and was not morally corrupt, a matrilineal tradition amongst many high caste Hindus in Kerala, a church that grew in adherents and advanced greater equity amongst its values and aspirations and promoted interreligious tolerance that also received the support of Hindus, and a progressive people’s movement that advanced social reforms.

According to Taylor and Taylor, this social movement initially fought back against caste-based discrimination but continued beyond that, advancing public literacy and education, promoting land reform, and making scientific knowledge broadly available to the public which has also played a role in public advocacy for continued environmental conservation.

Momentum built on momentum in positive interlocking ways: advancing women’s rights, promoting expanded educational opportunity, and providing enhance economic opportunities for trade that were open to a broad cross-section of the population all acted synergistically to advance human development.

The high literacy rate, for example, has enabled the average Keralan to follow newspapers and hold political leadership accountable in democratic elections and in between elections.

The evidence Taylor and Taylor provide is substantive and significant: In 2001 while life expectancy was 74 years in Kerala it was 59 years in all of India. Literacy in Kerala amongst females was 87%, while it was only 39% in all of India. In 2011, Kerala was the only state in India in which there was no preference for male babies; in 1991 its gender ratio was 1,036 females to 1,000 males, compared with 927 females to 1,000 males for India as a whole.

Kerala’s successes are impressive, sustained, and genuinely life altering for individuals and for society.

Taylor and Taylor note that economic wealth did eventually result from these substantial advances in human development in Kerala.

Today Kerala enjoys both high levels of social development and economic growth and greatly increased financial resources.

It is instructive to turn to Kerala’s history to learn that opportunities abound even in places that are initially resource-poor.

Human development can be enabled and derive energy from largely indigenous sources.

To be sure, Kerala’s model is unique to Kerala and its circumstances.

But undoubtedly, it has lessons for all countries seeking to advance human development and to the United States and other countries when conceptualizing and implementing development aid.

These lessons are encouraging in their affirmation of local capacity to advance positive social change from within that draws upon domestic human resources, some – but relatively moderate support from abroad, and the values and social policies that advance equity, social justice, and human emancipation which ultimately can unleash human development and well-being.

Development Series- Part III: SEED-SCALE in Nepal

Development Series- Part III: SEED-SCALE in Nepal

Adapted from Empowerment on an Unstable Planet: From Seeds of Human Energy to a Scale of Global Change, by Daniel Taylor, Carl E. Taylor, and Jesse O. Taylor

(All photos throughout post taken from various Future Generations activities in Nepal.)

Traditional development has not dealt kindly with Nepal and has not succeeded despite huge investments of both human and financial resources over many decades.

If the best current development practices were effective, then they should have worked in Nepal. Six decades, several billion dollars, and the careers of some of the world’s finest development professionals were invested in the kingdom to reduce poverty, illiteracy, and illness. Yet today, 30 percent of Nepal’s population remains below the poverty line, with one-fifth of the country living on less than a dollar a day; half the population is illiterate, and mortality for children under age five is sixty per thousand live births.

How is this possible and what were its causes?

There were plenty of good intentions in all the right places. Economic growth was to reduce poverty. Education and elections were to build accountable government. Health services were to double life expectancy. For each, targets were set, and programs were generously funded. But while there was progress in many measurable program indicators, in each sector dysfunction grew in terms of how system relationships were functioning. Programs that were started fell apart when funding was diverted to other programs that interested donors. Newly built school buildings and schools a few years after being built by donors looked abandoned.

This dynamic is not unique to Nepal. Indeed, it characterizes the failures of traditional development programs around the world which Nepali development projects typified.

Intentions were good, outcomes were not.

Looking at Nepal as a case study helps to understand why community-based development that is genuinely communally oriented and involves real local participation and implementation is far more likely to succeed and be sustainable than traditional development projects reflecting huge, external outlays of cash and foreign expertise, but without local participation.

Without an integrated role for the Nepali government on national and regional levels to work in a three-way partnership both with local Nepali communities and with external development and aid agencies – and the resources and expertise they bring – development in Nepal was not sustainable.

The Taylors argue that although Nepal lacked financial and human resources initially, in the 1950s, when development projects began, Nepal actually had access to extensive financial and human resources available since that time, for over sixty years. In other words, the failure of Nepal’s development trajectory is not because development was working and was simply underfunded and/or not sufficiently expanded across the country. The problem was and remains that it was not working effectively, and it was not responsive to community needs.

According to the Taylors, by 1999 the bottom fifth of Nepal’s population suffered from greater poverty, malnutrition, and lower overall human development than in 1949. Traditional development programs implemented during these fifty years did not consider how the Nepali economy in the 1950s and through the 1990s was systematically excluding a huge sector of the Nepali population.

The core reason why the quality of life had gone down for the bottom quintile was that the currency of change had shifted. In 1949, a barter economy based on human energies gave employment options to poor people; but by 1999 the monetary economy had removed labor-based options; money was now required to participate in the modern world.

Had traditional development efforts been sensitive and responsive to this reality and the challenges it created for one fifth of the population, Nepal’s development trajectory would likely have been a much different and better one.

But they were not.

Further, even the development efforts they pursued that reached some of the remaining 80% of Nepal’s population, had relatively poor results and often ended in neglect or desertion because they did not link local communities in a meaningful, participatory way with the regional and national government and with foreign aid agencies and were not communal oriented.

Pockets of development would often take place in an isolated, temporally-bound manner creating the illusion of development momentum and positive change. Once the money and human resources stopped coming in, the development projects ended, development indicators declined, and local communities had neither gained in capacities nor resources to advance their own development and sustain it.

By definition, a program of development that relies primarily on external support and that does not reflect local communal needs and participation will eventually peeter out when funding ends and when human resources experts complete whatever block of time they have committed to a particular development project and country. When they leave and when funding ends, projects decline and eventually – often – die out altogether, with no one locally available to maintain and continue them.

Thus, there were decades when it appeared that traditional development was working: roads were being built, schools constructed and staffed with teachers, the economy diversifying, and Nepalis working abroad and returning to Nepal remittances that assisted Nepalis in Nepal to raise their incomes and their human development. Hotels and restaurants opened in Katmandu raising incomes and increasing employment there.

But these economic changes and expansions were not well distributed across the country in an equitable way and many were not long lasting.

The lack of democratic accountability, a rigid and exclusionary caste system, and high levels of corruption all contributed to the failure to advance development that was genuinely and sustainably transformative.

The international community acquiesced in maintaining old-order structures. For example, during these decades not one embassy or aid agency had more than a handful of token low-caste employees in managerial positions or engaged in systematic affirmative action hiring. Development was growing into a world of appearances: outputs were measured and contracts fulfilled, but connections between programs tended to be ignored.

When the monarchy was overthrown what resulted was civil war, mass violence, and chaos. Although efforts were made to write a new constitution and find more effective forms of governance that were truly inclusive and responded to the needs of the people, corruption, dysfunction, inequality, injustice, lack of responsiveness to local and regional needs and preferences, and collapse of the rule of law characterized Nepal.

By 2010, a once-expanding infrastructure built by foreign assistance was crumbling: roads, government offices, clinics, schools, postal services, agriculture extension services, even tax collection. An increasingly corrupt government system could not maintain infrastructure that aid had built. Ancient divisions of caste and tribe persisted, crippling social advancement as half of the national population, women, still were only symbolically included in decision making.

In contrast to the failures of traditional development efforts, Nepal has had substantial success in local, community-based development efforts – though these have not been extensive enough to lift the entire country out of poverty and they have received far less support from both the Nepali government and external donors than traditional development efforts. Many of these efforts are ongoing.

Nepal is filled with such examples [of community based development]: community-based clinics and schools, forests, microcredit schemes, and water supply systems. Even more persuasive proof of people’s energies are the thousands of trails, temples, village waterspouts, and herculean terraces built without any external assistance… Another example of the diffuse, emergent manner in which the people pulled themselves forward lies in Nepal’s ecotourism industry.

But these successes, outside of several select cases such as eco-tourism, have not been able to scale-up and are limited to local, grassroots initiatives.

Nepal is perhaps unusual in that although it has a record of failed traditional development – as many countries do – it simultaneously has a record of successful community based development which many countries do not.

Nepalis knows how to lift themselves out of poverty and advance their development.

SEED-SCALE has been well demonstrated in Nepal in a variety of contexts – from community-based road and bridge building efforts that have been high quality and extremely cost effective – with lasting benefit expanding trade and enabling improved travel for access to healthcare and markets to sell goods and services and produce grown in the countryside – to a sophisticated eco-tourism enterprise and range of extensive tourism related businesses incorporating tour guides, restaurants and hotels.

Many Nepalis have adapted to the opportunities provided by tourism to increase their income and use that income to improvetheir quality of life through better healthcare, housing, and educational opportunity.

While many of these programs have not been able to expand beyond largely localized programs, if the Nepali government on the national and regional level and foreign donors and aid agencies learn from the mistakes of the past and build on the successes of SEED-SCALE, Nepal will be able to advance its own development sustainably and successfully.

Then the community development that is currently taking place on a relatively small scale could eventually characterize the country as a whole for the better of all its citizens and contribute to equitable, expansive, participatory, and sustainable human development.

Development Series- Part II: Community Development from the Grassroots

Development Series- Part II: Community Development from the Grassroots

This week, we’re excited to announce that Professor Schimmel’s second post in the Development Series can be found on McGill University’s Centre for Human Rights & Legal Pluralism blog! Follow the link below to read his assessment on how the SEED-SCALE theory of social change can benefit the larger field of development.

https://www.mcgill.ca/humanrights/article/community-development-grassroots